A Programme Associate with the UNU Institute of Advanced Studies, Operating Unit Ishikawa/Kanazawa, Laura Cocora has been based in Japan since 1998 and holds a masters degree in Global Studies from Sophia University. She is interested in the interactions between the cultural and environmental dimensions of societies and the role they play in sustainable social and economic development.

Biodiversity in Kanazawa: Summer’s Lesson

Food production and consumption comprise a major dimension of human life in which biological and cultural diversity intersect and are mutually reinforcing. The influence of biodiversity on Kanazawa’s food culture spans all the scales on which biodiversity occurs — from landscapes to local crop varieties. The city’s vibrant local cuisine displays creative combinations of ingredients and tastes, reflecting the diversity of the plentiful supply of fresh foods provided by the surrounding sea, fields and mountains. Local food culture, as manifested in the tastes and desires of the city’s people, has played an important role in the continuous cultivation and use of traditional vegetables, selected over the years for desired characteristics, as they were taking into themselves the very substance of the region’s soil and climate.

Many of these traditional vegetables reach maturity during summer, which in Kanazawa is a season of intense sunlight and heat, slowing down the rhythms of the city. Gastronomy is an important part of the colourful festivities bringing people together on summer nights, after the relentless heat has subsided. Some of these festivities focus specifically on agricultural production, and belong to a complex annual ceremonial cycle rooted in culture-specific views of nature.

A different interplay of biological and cultural diversity can be observed in the case of recreational river fishing practised in Kanazawa in summer. Summer fishing for sweetfish (ayu) in Kanazawa’s rivers shows how recreational practices, cultural heritage values and a sense of beauty can converge in food production activities.

Kaga vegetables: Agricultural biodiversity and cultural identity

In July, as the summer heat slowly approaches its height, white buds burst into bloom among giant leaves of green jade in Kanazawa’s lotus fields. Lotus has a long history in the city. During the Edo period, it was grown in the ponds of Kanazawa Castle for its ornamental flowers, and high-ranking samurai also consumed it as medicine. Several lotus varieties cultivated for their edible rhizomes were introduced to the area in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Of these, a locally selected variety, distinguished by the crunchy texture of its fibrous roots, continues to enjoy popularity as one of the city’s praised Kaga vegetables. In summer, its immaculate white blossoms greet visitors to Kanazawa as they arrive into the city from the east.

Fifteen of the traditional vegetables produced in Kanazawa since before 1945 have been designated as Kaga vegetables, a local brand established by Kanazawa City and the Agricultural Cooperative. Kaga vegetables feature prominently in the local produce corners of the city’s markets and food stores, reminding customers of the relationship between local vegetable varieties, food and the city’s cultural identity.

Photo: Ryo Murakami.

In recent years, various reasons have been invoked in global discussions for the need to safeguard the biodiversity of cultivated species by conserving and utilizing traditional varieties that are increasingly threatened by the widespread introduction of modern breeds. Traditional varieties have been shaped by farmers’ seed choices, while adapting to specific environments over generations of cultivation.

With their different abilities to withstand a range of environmental conditions, traditional varieties are a reservoir of options for the future, allowing human societies to switch to a different existing variety or to develop new ones when environmental change occurs. Not only can they contribute to better nutrition, income generation and environmental conservation, but they also hold important cultural values, being embedded in local cuisine, customs, lifestyles and social relations.

Cultural values played an important role in saving Kanazawa’s traditional vegetables from vanishing in the sands of time. The onset of Japan’s period of high economic growth in the 1950s marked the transition to modern hybrid crops bred for higher yields, uniform shapes and disease resistance. Kanazawa’s patrimony of local vegetable varieties was in danger of being lost in the competition with the more productive, standardized, placeless vegetables promoted by industrialized agriculture.

The driving force behind the movement for conserving the city’s traditional vegetables was Ryo Matsushita, the fifth-generation owner of a seed-and-plant store. Since 1861, when the store opened on the Hokkoku Kaido highway, which ran along the Sea of Japan and connected the northern provinces with Kyoto and the Ise Shrines in the south, the seed merchants of the Matsushita family partook in a tradition of exchange of information and seeds. A convenient stopping place for travelers, the store served as the gateway through which seeds from all over the country would enter Kanazawa to be selected and adapted according to local conditions. Faithful to his family’s past, Matsushita started collecting seeds and, in 1991, formed the Association for the Conservation of Kaga Vegetables that encourages farmers to save, share and cultivate traditional vegetable seeds.

The Association played an important role in the establishment of the Kaga vegetables certification system. Of the thirty-two traditional vegetables identified in the city, the fifteen designated so far are those for which existing production was deemed sufficiently robust to render them economically viable. Efforts have been made to raise the profile of Kaga vegetables, marketing them both locally and nationwide, disseminating information on their history and characteristics through websites, and developing specific cooking recipes to stimulate demand.

Photo: Ryo Murakami.

Unlike new breeds that can be found in supermarkets all year round, Kaga vegetables follow the natural rhythms of the year. The excitement of the seasons is enhanced as colourful vegetables slowly ripen in the fields. Summer is the harvest season for six of the Kaga vegetables, and market stalls are piled high with the greens and purples of kinjiso and akazuiki leaves, the bright red of chestnut-flavoured Utsugi pumpkin, plump and glossy violet-stem eggplant, the delicate greens of young Kaga hyacinth beans and the earthen shades of lotus root. As the cool of autumn settles in, these are replaced by red-skinned Gorojima sweet potatoes, white gensuke daikon radish and Kanazawa thick leek, and the smooth beige of kuwai arrowhead bulbs. Winter is the season of long, slender and soft Japanese parsley, while the verdant flush of leaf mustard, garland chrysanthemum leaves and Kaga thick cucumbers, along with chunky and pale bamboo shoots, announce the arrival of spring.

Kaga vegetables are also closely connected with the features of the city’s landscape, to the different soils, climates and landforms. Leek and eggplant thrive in the volcanic ash soil of the hills in the southeast of the city, left behind by past eruptions of Mount Haku. Sweet potato fields extend on the sand dunes along the coast. Kinjiso leaves grow along the foot of the mountains, where they absorb moisture from the spring mists and deepen their colour as temperatures vary between day and night. Lotus root and arrowhead prefer the low-lying marshy fields in the northeast. Given their adaptation to natural soil conditions, traditional vegetable cultivation relies on less chemical inputs, contributing to soil conservation.

One of the reasons traditional Kaga vegetables are threatened is that they require far more work to cultivate and harvest than new breeds. Arrowhead, for example, grows in flooded fields with a deep layer of clay-like soil. Kaga thick leek is particularly brittle and vulnerable to strong winds. Despite these difficulties, farmers in Kanazawa are willing to carry on cultivating the local varieties that have been central to the city’s culinary traditions.

Relationships between traditional vegetable varieties and local food culture have a cultural side that goes beyond preferences for certain aesthetics of taste. Kaga vegetables play an important role in the famed local Kaga cuisine. Conjuring up images of the opulent culture of the lords of the Kaga domain and of exclusive Japanese-style restaurants, Kaga cuisine is in reality a recent term introduced to promote Kanazawa’s traditional home cooking, which features signature dishes such as duck meat stew and steamed sea bream.

Photo: Ryo Murakami.

Kaga cuisine emphasizes not only the food, but also the experience of the entire context of the meal. Restaurants specializing in Kaga cuisine retain something from the atmosphere of old Japan, with wooden architecture and scenic garden views. The choice of ingredients, tableware and garden designs is in harmony with the seasonal shifts in climate and the changing faces of nature. In the endeavour to capture the sights and aromas of the seasons, Kaga vegetables are indispensable. The Kanazawa lacquer-ware — with its lavish decoration of gold and silver motifs — and the colourful Kutani porcelain on which the food is presented also have a seasonal theme. Encompassing all these elements, Kaga cuisine is a carefully staged performance, reflecting both the diversity of its environs and the cultural influences that have ebbed and flowed throughout history.

There are many factors behind the continued presence of the colours of Kaga vegetables on Kanazawa’s fields, market stalls and tables: a nostalgic attachment to the tastes of the past, the touristic lure of culinary specialties, the food mileage movement, and a successful branding strategy, to list but a few. They all show that cultural values of food can contribute to valorising and conserving local varieties of cultivated species and biodiversity at large. The future of our food systems might depend on our creativity in unveiling the roles of biodiversity in what we cherish about our communities and places, and in incorporating them into meaningful experiences.

Seasonal celebrations of nature and culture

On hot midsummer nights, the thick air is rich with the scents of the fields, flickering torches and the sound of drums. It is the time when mushi okuri rites are held to chase away pests and protect harvests in the agricultural communities on the fringes of Kanazawa City. During the day, groups of children and youngsters parade along the streets, carrying white banners inscribed with wishes for plentiful harvests, protection from harmful insects, prosperity and peace. As dark descends, adult members of the community join in a procession with drums and torches along the footpaths between the rice paddies as they chant: “Abundance of the five grains! We are sending rice pests away!”. The powerful sounds of the drums reverberating through the night are meant to dispel the evil spirits whose workings were considered the cause of pest outbreaks. A roaring bonfire, set ablaze towards the end of the ceremony, dances against the night sky.

Photo: Kanazawa Kurashi Museum.

Mushi okuri rites are one of the many annual celebrations that mark the rhythms of the seasons in Kanazawa. Although today the widespread use of pesticides has eliminated the threat that a sudden insect outbreak could totally ruin the harvest, causing the decline of mushi okuri rites throughout Japan, the practice is still observed in some of Kanazawa’s communities after the midsummer weeding of the rice fields, when the insects are most abundant. Mushi okuri is associated with the growing season, the middle period of the agricultural cycle in which many of the calendrical festivities of the farming communities in Kanazawa’s peri-urban area are grounded.

In spring, at the time of planting, local Shinto shrines become the stage for community festivals meant to ensure abundant crops later in the year. Autumn festivals are held before and after the harvest as an expression of gratitude. As occurs elsewhere in Japan, such festivals involve summoning the tutelary deity of the land, often a nature or ancestral deity that controls the fertility of the fields and natural calamities. The deity is paraded through the streets in a palanquin and entertained with food, drink and performances in order to enhance its power and secure its favourable intercession.

The annual calendar brings together a variety of seasonal festivities based on different spiritual traditions into a single temporal sequence. While agricultural festivals related to planting or the harvest are associated with the natural polytheism of Shinto, summer is the season of the most important Buddhist festival of the year: the Obon Festival, which honours the spirits of departed relatives and ancestors. At this time of the year, ancestral spirits are said to return to this world to visit their homes. It is holiday season in Japan, and people return to their hometowns to spend time with their families and look after the ancestral graves. Houses are cleaned, altars decorated and lanterns lit to guide the spirits on their way home. Offerings of food and flowers are made at the family Buddhist altar and sutras are chanted. Stands for drummers are set up in temple yards and other open public spaces, ringed by circles of people performing Obon dances to welcome the ancestors.

In the central areas of Kanazawa, the Obon Festival is celebrated in mid-July, while in the peripheral rural areas that have been incorporated into the city’s administrative area over the last century the date continues to be determined based on the lunar calendar, corresponding to mid-August. According to local custom, small rectangular paper lanterns known as kiriko are lit at the graves to guide the souls on Obon nights. As the hills of Utatsuyama and Nodayama come alive with the soft glow of the kiriko lanterns, the city is filled with the music of Obon dances floating in the air and the swish of summer kimonos. Summer is a time of sensuous encounters between nature and performance, which shape the cultural landscape of the city.

Annual celebrations are reflective of broad worldviews, of concepts of the cosmic order and the human place in it, arising from present and past spiritual traditions and systems of belief. Such worldviews and concepts evolve within the specific ecologies of each community’s natural environment. They reflect back upon the environment through our spiritual connections to the natural settings that we value as sites of ritual, ancestral worship and communal celebration.

Kaga fishing flies: Kanazawa’s rivers and recreational practices

On a clear summer morning, in one of the green bends that the Asano river forms at the foot of a hill, an angler wades through the water with a fishing rod, trying his luck for the ayu sweetfish that leap occasionally into the air with a silver gleam. He whips his line in a smooth arc and the colourful fly cuts through the air, dropping like a real insect on the water under the willows.

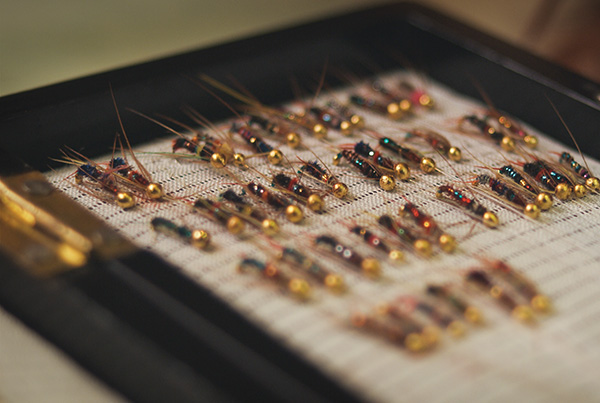

The manufacturing of artificial flies for ayu fishing has a long tradition in Kanazawa. The store that produces and sells the Kaga fishing flies near the Omicho Market boasts a history of nineteen generations of merchants since its establishment in 1575. A visit to the store reveals an impressive array of lures resembling exotic, brightly-hued insects, with their hooks wrapped in colourful threads and decorated with bird feathers.

The flies are crafted based on the careful observation of various factors: from the behaviour of fish and the stage of their growth, to weather, time of day, location, temperature and depth of the water. Over the centuries, the store has developed an estimated 4,000 distinct fly types, suited to each combination of natural conditions. In their varying colours and forms, the flies encode and transmit a rich knowledge of nature, including the preferences of the ayu, but also changes over time in the water quality, transparency and temperature of the river environment.

Photo: Ryo Murakami.

An important role in the development of the Kaga fishing flies has been ascribed to the samurai of the Kaga domain. According to local lore, ayu fishing was recommended to members of the warrior class for its spiritual and health value, as training for the body and the mind during the peaceful times of the Edo period. Bringing in the fish with the barbless Kaga flies required concentration and a good sense of timing. The samurai became absorbed in their pastime, perfecting the flies and thus paving the way for the development of what remains today one of Kanazawa’s rare traditional crafts.

Kanazawa’s rivers have influenced the city’s cultural history, including its recreational practices. A nineteenth century folding screen depicting scenes from the Sai river shows people with woven sedge hats fishing for ayu, and groups eating lunch boxes on the river banks. The figures represent clansmen and their families, since such forms of river entertainment were prohibited to commoners under the rule of the Kaga clan.

With the abolition of the clan system in 1868, Kanazawa’s rivers became accessible to everyone, and bathing, fishing and feasting on freshly caught ayu and gori fish by the river’s side became common summer sights. Old photographs from the beginning of the twentieth century show the Asano River filled with people bathing. Enjoying the relative coolness of summer nights on the river in pleasure boats hung with lanterns seems to have also been a popular entertainment form.

Many rivers in Japan’s larger cities are today encased in concrete and roofed over by highways, but Kanazawa’s rivers remain enchantingly alive. From the bridges spanning the Asano and Sai rivers, one can spot the dark shadows of the fish swimming in the current. Small flocks of ducks glide lazily on the water surface. With ritual-like, elegant movements, solitary white egrets and great blue herons step through the shallows. Dragonflies hover motionless over the tall grasses.

Seeing people get into the river for one reason or another is not unusual in Kanazawa. Even on winter mornings, some Kaga yuzen dyers would start rinsing swaths of colourful silk cloth in the Asano river to remove paste and excess dye, but this scene is becoming increasingly rare today. It is during the stifling summer heat, that the rivers entice most with their irresistible lure. Groups of children walk into the river with their teachers to learn about water organisms. Men pile stones together on the riverbed to guide the flow that will carry the floating lanterns during summer festivals. Couples sit on rocks with their bare feet in the water, the breeze ruffling their hair. Ayu fishers still cast their rainbow-coloured flies through the air with crisp, sword-like movements.

For centuries, the multifunctional landscapes of Kanazawa’s rivers have provided food and space for recreation. Today, they continue to be oases of beauty and abundance in the cityscape, where people can immerse themselves in the natural settings, experience their sounds and sensations, and enjoy life.

♦ ♦ ♦

The video featured here is an extract from the “Book of Seasons” documentary and the text is from the “Biodiversity in Kanazawa” booklet that are part of a multimedia project on biodiversity in Kanazawa that was initiated, designed and funded by the UNU Institute of Advanced Studies Operating Unit Ishikawa/Kanazawa (UNU-IAS OUIK) under the coordination of the Unit’s Director, Anne McDonald. The project creatively “packages” OUIK’s cutting-edge research and explores complex aspects of the urbanization-biodiversity nexus in a form accessible to researchers, students, policymakers and civil society, both in Japan and around the globe.

Biodiversity in Kanazawa: Summer’s Lesson by Laura Cocora and Anne McDonald is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.